Visiting Namibia, the World’s Oldest Desert, and Climbing Dune 45

Fifty-five million years. It’s a long time, no matter how you look at it. For 55 million years, particles of sand, in shades of blood red, caramelised orange and an exhausted, jaded rust have sifted one over the other in this part of the world.

I stand clasping a few of them, gasping for breath.

The Namib Desert

I’m in the middle of the Namib Desert, the oldest desert in the world. It’s the desert whose very name means wide open space and whose powerful two syllables, sands and scorched shadows almost define the country it lives in.

Namibia. The land of wide open space.

Climbing Dune 45

The reality is that I’m nowhere near the middle of the Namib Desert, an expanse whose boundaries stretch for over 32 000 meters from the Forbidden Territories in the south to the Skeleton Coast in the north.

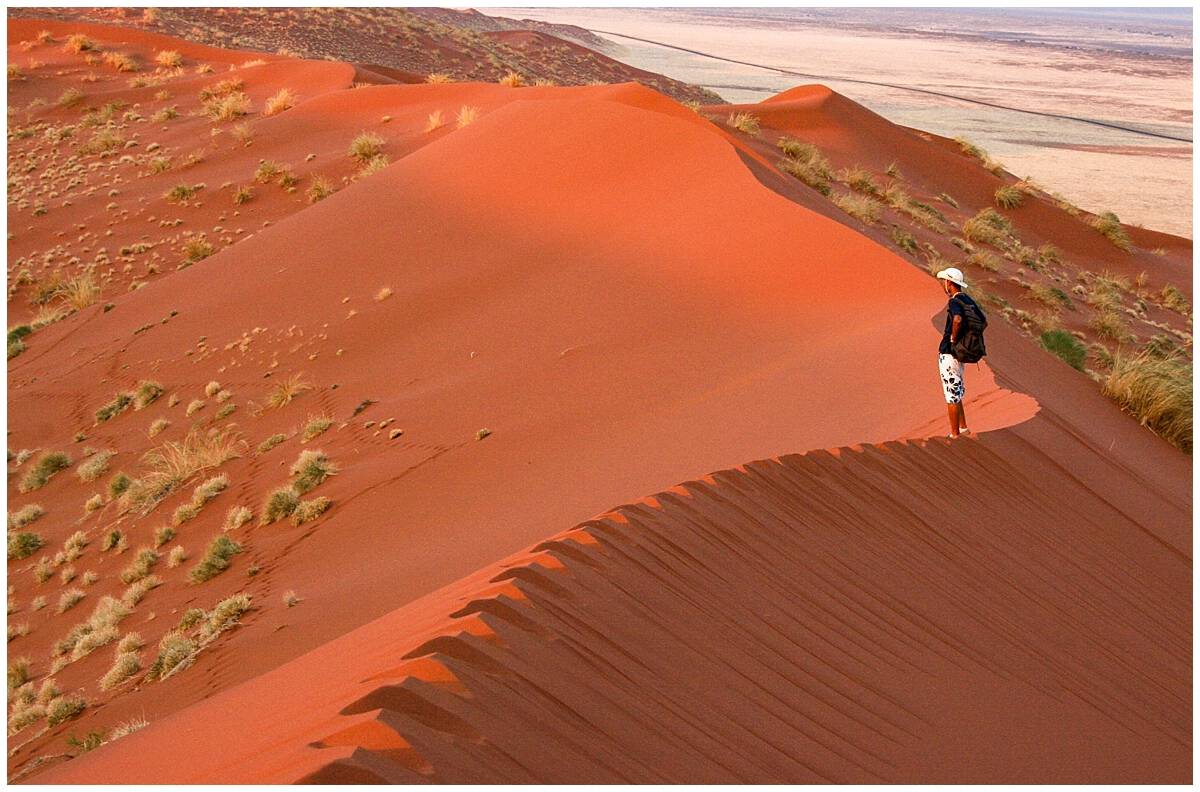

I’m at – and on – the edge, huffing and puffing, slipping and sliding, stumbling and generally bumbling around as I try to climb Dune 45, the most accessible dune in the Namib Naukluft National Park.

Accessible, of course, is a relative term. Almost insulting as I think about it now, my lungs straining at the seams, my capillaries compressing every blood cell in the quest for more oxygen.

Dune walking, like moon walking, is harder than it looks and we’re racing against the sun to reach the top first.

Racing the Sun in the Namib Desert

It doesn’t seem like a fair contest. The sun has been practicing for more than 55 million years, whereas I only arrived last night. The sun didn’t need to rescue the 4 x 4 from spinning ruts in the sand, nor negotiate with officials over paperwork at the entrance to the park. It didn’t need to feel old as it scrambled past students who giggled their way to the top.

On second thoughts, after 4.6 billion years, perhaps the sun does feel old. The Namib Desert must look like a cheeky little upstart; the travellers who scramble across its sand, ducklings in the wake of burning waves.

You can climb Dune 45 easily within half a day. However, it’s best to avoid the middle of the day and wear appropriate clothes (including footwear) and bring plenty of sunscreen and water.

Watching Wildlife from Dune 45 And Beyond

Dune 45 may be popular, but elsewhere the desert is empty. Empty of humans, at least.

Standing proud on the horizon, an oryx silhouettes itself against the violet sky. We leave Dune 45 and move closer, the colours growling with intensity as the sun reasserts its authority over the day. Four or five oryxes stand beneath their leader, ears twitching, bodies still, faces turned towards us.

Against the red, their monochrome faces and spiralled- yet-straight antlers pierce the ocean of colour. Majestic. Permanent. More suited to this environment.

I reach for my camera.

In a flash of hooves and a low rumbling of dust, they’re gone, on to the safety and shadow of the next rippling dune.

Flying Over the Namib Desert and Dune 45

From the air, it’s easier to track oryxes – and even to pick out an ostrich and some springboks as they gallop along the horizon. A flight from Sossusvlei Lodge reveals choppy crimson waves beneath a cloud of smoky red haze. Yet there’s more to the Namib Desert than that. Hidden behind the “accessible” dunes, there’s sandy golden patches with unexplained circles drawn into the sand. There’s scrubland and canyons and breadcrumbed dunes with scratchy balls of bleached quill grass.

And, most captivating of all, there’s Sossusvlei.

Sossusvlei & Dead Vlei in Namibia

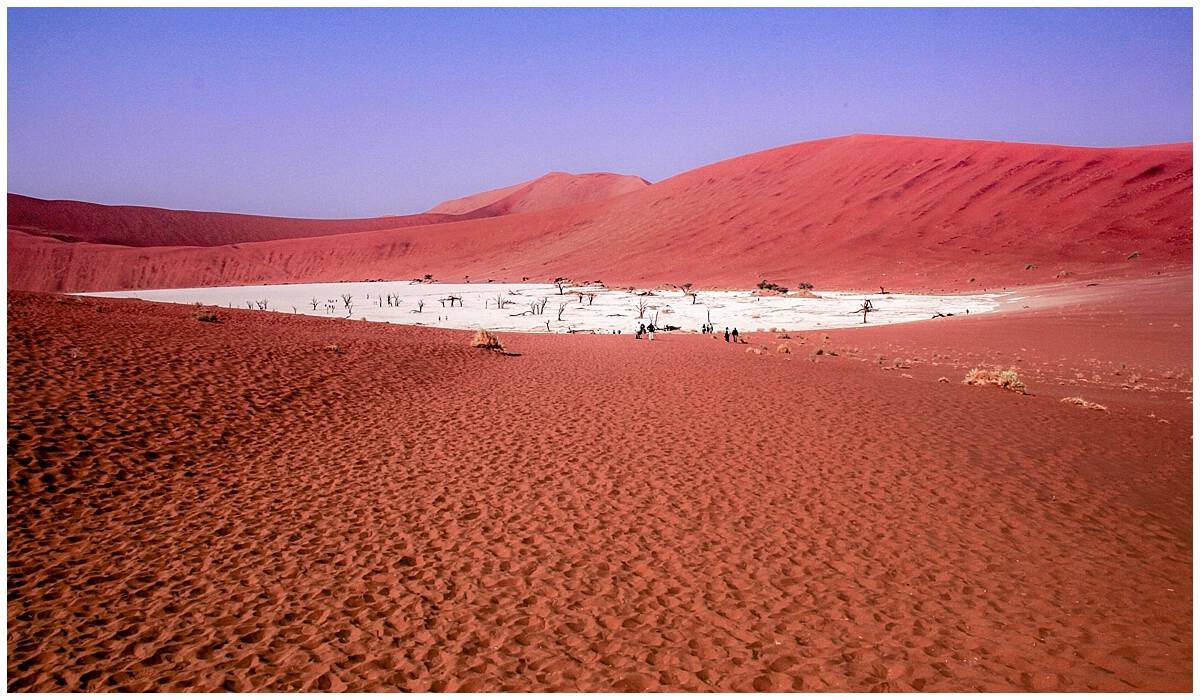

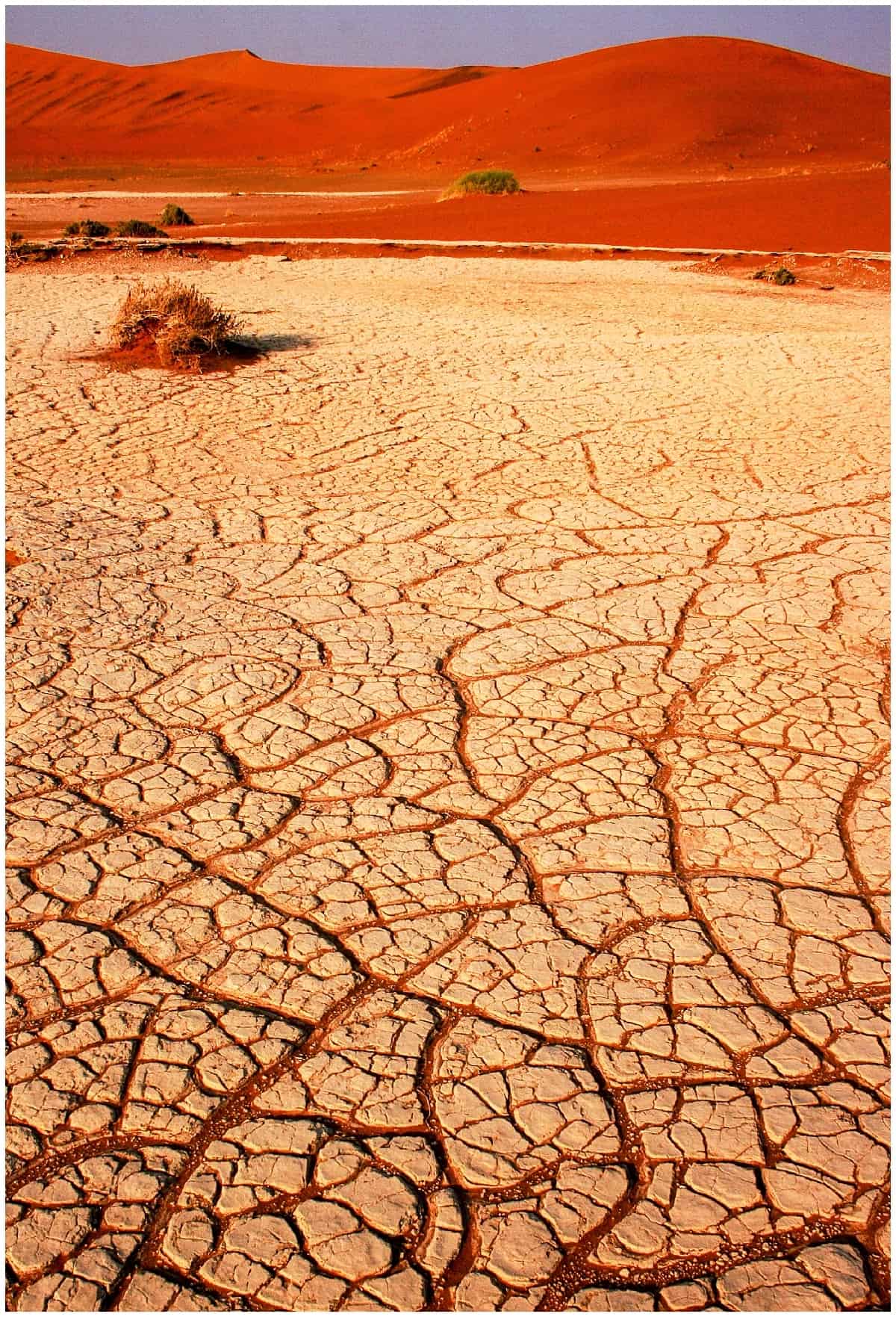

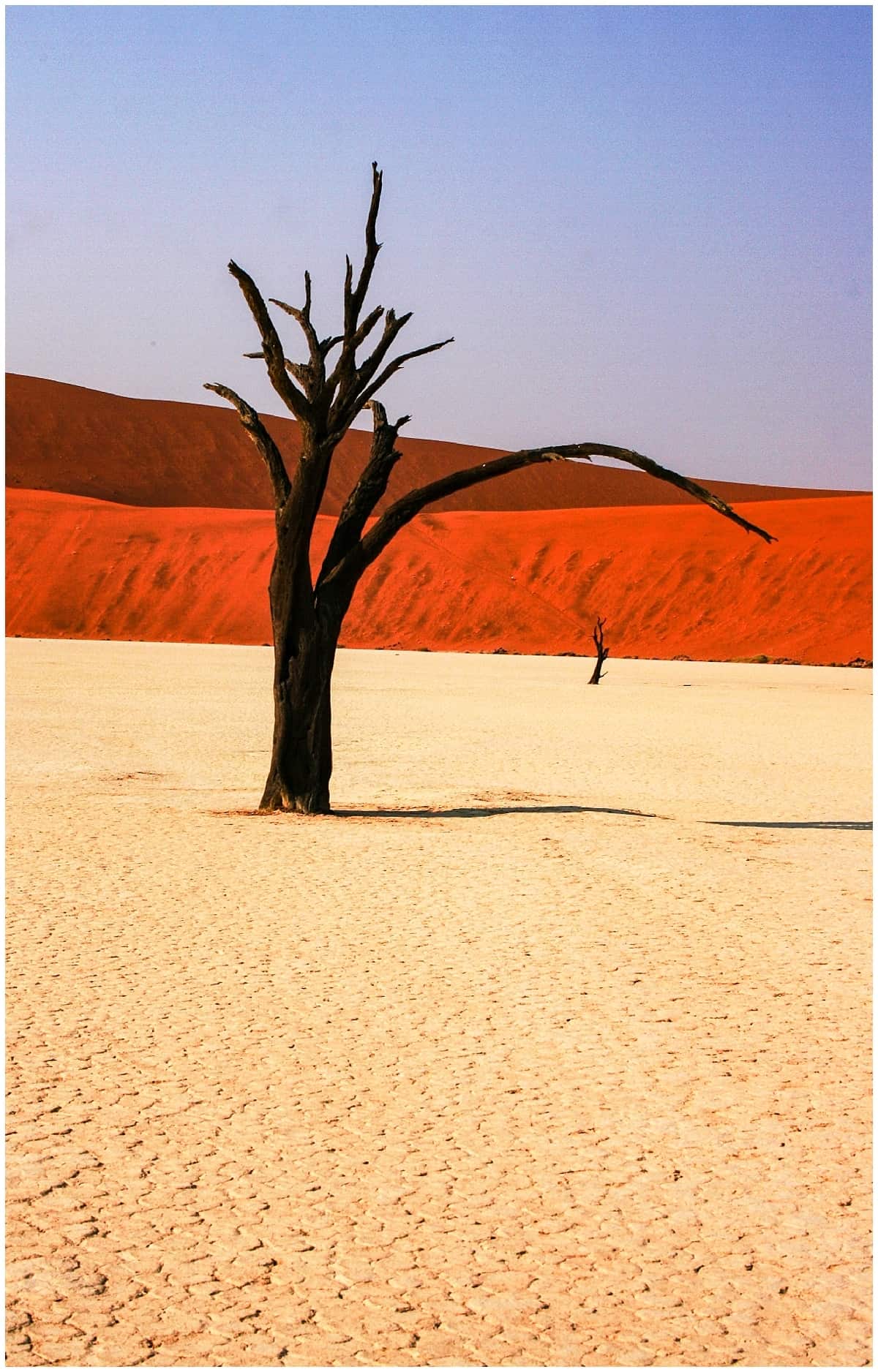

Depending on who you ask, Sossusvlei means “Dead Valley” or “The Point of No Return.”

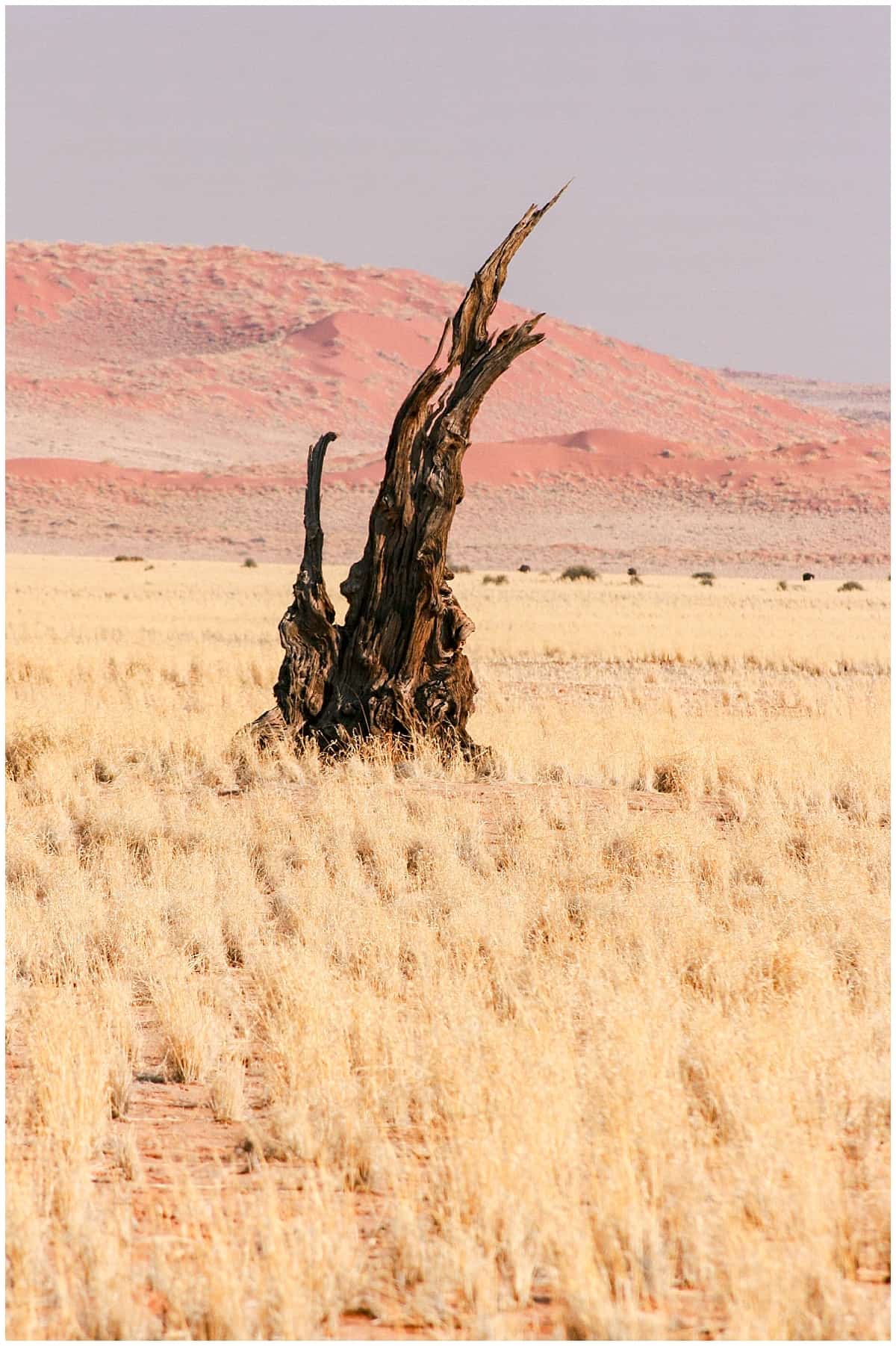

It’s a creamy, jigsaw carpet spread across a valley of scarlet, punctured only by the ghosts of undead trees. Their charred, dark branches reach into the sky, making forks like serpents’ tongues. They cast a spell so powerful over the index fingers of those who visit that they cannot help but take 55 million photographs and press their eyes against the viewfinder for hours on end.

Or perhaps that was just me.

This particular part of the desert is called Dead Vlei, and there’s not so much discussion about what that phrase means.

As recently as 1000 years ago, water flowed, or at least trickled, through the depression at Sossusvlei. As the temperature rose, the valley beds dried out, forming a natural clay jigsaw that became the playground of photographers’ dreams.

“The trees are dead,” our local guide tells me. “But without water, they cannot rot.”

From Sossusvlei to Sesriem Canyon

“They cast a spell so powerful over the index fingers of those who visit that they cannot help but take 55 million photographs and press their eyes against the viewfinder for hours on end. Or perhaps that was just me.”

I look around with new eyes and notice a whitebait spider scuttling into a crevice to hide from the sun.

“They’ve been this way for almost 900 years,” the guide adds.

Nine hundred years. Before I came to the Namib Desert, I might have thought that was a long time.

At ground level, the two million year old Sesriem Canyon sinks into the earth with a creamy, crumbly crust

The trees in question have bolt upright trunks with stubby branches coloured a dark chocolate brown – Cadbury trees on the milky surface of the valley. In the distance, oryx stare at us, tilting their spiral horns in disbelief at our trespass through this natural graveyard.

While the trees may be dead, there’s still plenty of life scurrying across the sand (and I’m not just talking about the tourists on Dune 45.)

Etched into the surface of the desert are signature tracks from oryx and springbok, squiggles from snakes and scratches from ostriches. A whitebait spider waits, camouflaged with the stone, while birds with orange eyes swoop to steal unguarded food.

By night, jackals howl and scratch outside the tent, crunching the bleached grass as they saunter past, while just before sunrise, engines roar and rage as their wheels get stuck in the sand.

Chasing Sundown from Dune 45

We drive back towards the park gates in another race against the sun. Everyone must be out by sundown, say the park authorities, and the fines for disobedience can be severe.

Our wheels bounce across the sands as the colours fade to grey and the sun then slinks away.

The cries of jackals fill the air and I shiver beneath the darkness.

For all the talk of wide open spaces and the sands of the desert, I know there’s much more to Namibia than that. Wild plains with elephants, adrenaline-fuelled activities on the coast, tribal customs, cultures and disputes, and the remnants of British and German colonial architecture. And that’s just the start.

By the light of the stars, I sip Rooibos tea in the world’s oldest desert and realise that its home, Namibia, only became a country in 1990.

A 55 million year old desert in a country that’s little older than a decade. That’s young, whichever way you look at it.

And whether that’s by starlight, sunrise or sunset, it’s a fascinating place to look at.

Highlights near the Namib Desert

Etosha National Park

For the quintessential African safari, head to Etosha to watch zebra, rhinos, lions and elephants roam across the land. It’s Africa at its best.

Swakopmund

Namibia’s adventure playground – when the sun shines. Go sandboarding, ride camels, skydive or just tuck into the German strudel left over from the colonial period. (The custom, that is. The strudel is usually fresh…)

The Skeleton Coast

For a view of old shipwrecks and wild and rugged weather, head north along the coast towards Angola.

Fish River Canyon

Hike through the second-largest canyon in the world in the southern part of the country.

INFORMATION FOR VISITING THE NAMIB DESERT & Dune 45

Trip details

Three day tours to Sossusvlei leave from Windhoek every few days. Most tours include food, transportation, park fees, a guide and camping equipment. They tend to fill up quickly so do book in advance. Alternatively, hire a car from any of the major car rental companies in Windhoek and drive to the desert yourself. The journey takes around five hours and traffic drives on the left.

When to go

May through to September is the best time to visit Sossusvlei as the fierce summer sun (that can reach a stifling 60 degrees centigrade) has settled down a little. Bring plenty of warm clothes, though. Deserts, while hot during the day, get very cold at night and can approach freezing in the winter. Namibia’s rainy season is typically between November and April, making some of the gravel roads impossible to pass at this time. On the other hand, this is the time to visit the coast, where sea breezes offer some relief from the heavy heat inland.

Getting there

Sadly, a lack of direct flights to Namibia’s capital, Windhoek, makes this tricky. To reach Windhoek, a popular route involves flying with either South African Airways or British Airways to Johannesburg and taking a connecting flight on to Chief Hosea Kutako International Airport from there.

Domestic flights are rarely necessary within Namibia, but many people fly on to Maun in neighbouring Botswana to reach the Okavango Delta, although a good tarmac road connects these two popular places.

Getting around

The main roads in Namibia are high quality, making hiring a normal car and driving around on your own a wonderful way to soak up the scenery and reclaim your independence. Otherwise, look out for tours in Windhoek and Swakopmund – most will include transport as part of the trip. You do need a 4 x 4 for certain parts of the country, and for the final approach to Dead Vlei, but a transfer service is available at the site if you arrive without. Top up with fuel whenever you can, as petrol stations are in short supply. Public transport is also in very short supply…

Accommodation

You can usually find accommodation at short notice but do book ahead for a greater choice, particularly if you want to stay somewhere upmarket. Prices tend to be similar to those in Europe and the US. Namibia is not a cheap destination.

Luxury

At the entrance, the Sossusvlei open plan lodge with its earthy colours and glass features is one of the best in the area.

Camping

Most tours to the Namib Desert involve camping near the park entrance. You’ll find shower blocks, toilets and an on-site restaurant and gift shop. Camping areas are marked out by stones and gathered beneath trees for shade.

Cost of travel

Namibia, like neighbouring Botswana, is expensive for travellers. Park fees and guides make up most of the costs: staying in hostels and buying food from supermarkets is where you can keep costs down.

Packing Tips

Deserts, while fiercely hot during the day, become very cold at night. Pack long sleeved layers and don’t dismiss the idea of bringing a ski jacket, a hat and gloves. Leave the jewellery at home and you’ll have an easier time in the cities. Bring hiking boots, mosquito repellent and plenty of sunscreen and don’t forget your camera and binoculars for the safari drives.

Further Reading on the Namib Desert

Medical Information on Namibia

Namibia Travel Writing on Inside the Travel Lab

Have you ever visited the Namib Desert? Would you like to?

More About Travel in Africa

- The best places to visit in Africa: how to build your bucket list

- Namibia and the oldest desert in the world

- The best beaches in Madagascar

- What safari guides really fear in Botswana’s Okavango Delta

- How the red tsingy in Madagascar are the perfect antidote to travel overload.

- The real pride rock

- Why Ouirgane valley in Morocco deserves your time

- The highs and lows of driving in Morocco

- What you need to know about trekking Kilimanjaro

How amazing. It must feel almost like stepping outside time to this old old place. Would love to see it for myself one day but you’ve captured it so well.

Ah – it’s incredibly beautiful but also rather raw. For obvious reasons, it’s hard to go too far in to the desert. But just standing on the edge (or flying above) gives a glimpse into the alien landscape – it’s hard to reconcile that with the local Tesco back home! But that both, of course, are part of this planet… Hope you get there one day.

Very detailed and useful article! Camping here sounds amazing.

Yep! A real once in a lifetime experience