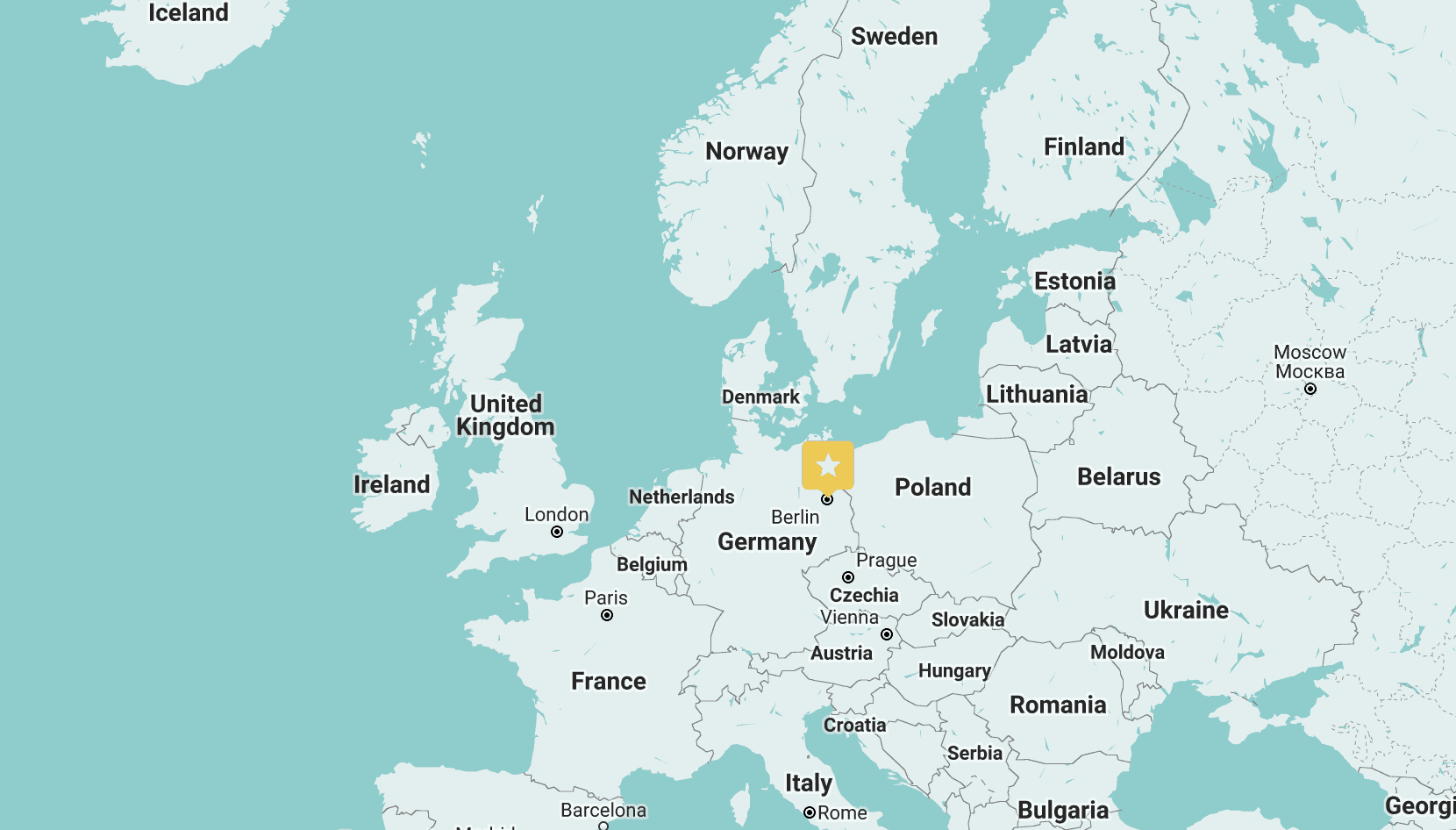

Growing up in east Germany? What was it like? That’s the question, of course from the west. But it works both ways. Here’s a conversation with those who grew up either side of the Berlin wall.

Growing Up in East Germany: The Other Side of the Berlin Wall

East. West. Good. Bad. Win. Lose.

Draw.

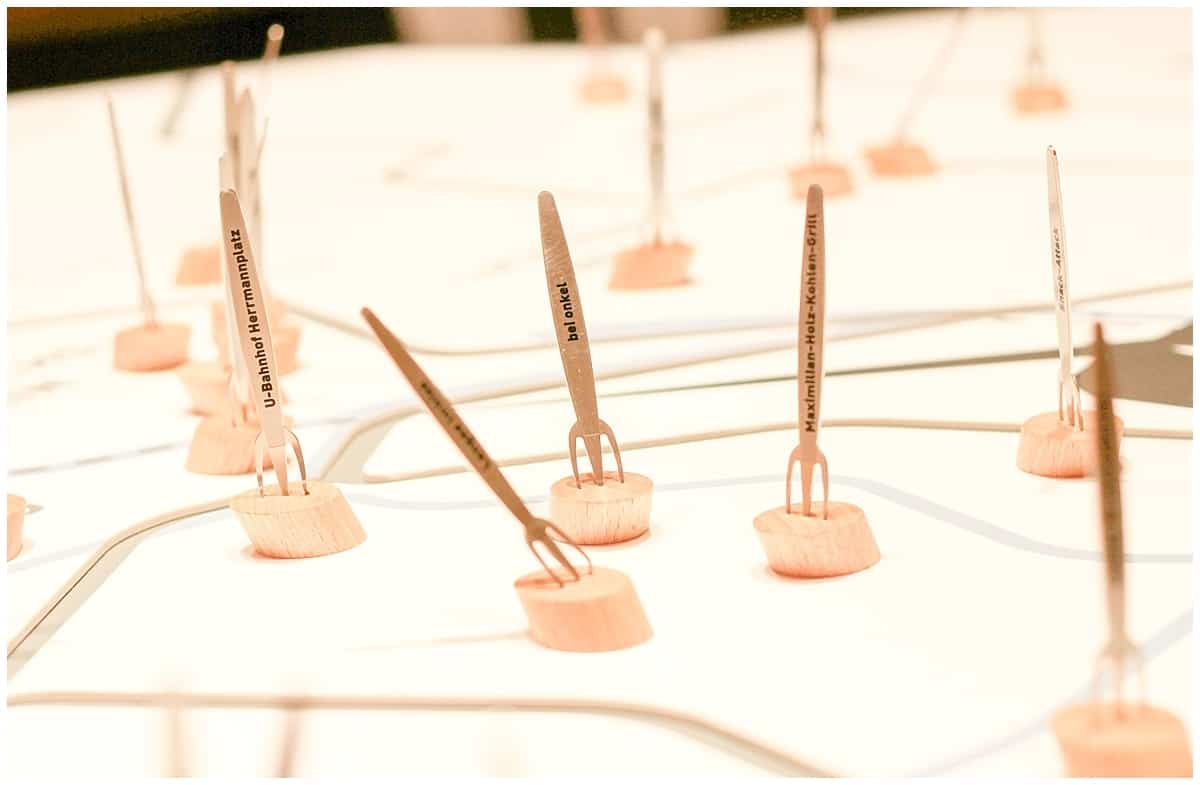

And so, at last, I am in Berlin. After more than a thousand miles by train, through some of the darkest moments in European history, some well known, others not, I find myself with a plastic fork in one hand and a fluffy orange sausage in the other in the Currywurst Museum.

The city of Berlin has a fascinating present, a promising future, and a documented, toxic past. Memorials to the holocaust rise out of the streets. So, too, do strips of tarnished metal that snake through the city where the Berlin Wall used to stand. All are symbols of respect, of regret and of remembrance.

But as it turns out, the key to understanding east-west relationships lies somewhere else. In the chilli powder cuteness of the Currywurst museum.

Children When the Berlin Wall Came Down

Across illuminated sausage on a miniature map of the city, I met people.

People like me.

My age. My sex. My skin colour. Not that I believe that any of that counts for very much.

No, what we really had in common was this: we all heard the news of the fall of the Berlin Wall when we were at school. We were the last generation of the Cold War – with the least understanding.

Yvonne in West Germany, Nicole in East Germany, and me in the UK.

The Real Story

After currywurst, we moved on to chocolate in the Fassbender & Rausch cafe, the sort that has seen it all since its inception in 1863. The sort whose chestnut dark tables and cream laden menus encourage conversation.

“Our school was very different to yours,” says Nicole as we unwrap the scarves and hats that bind us and give the chocolate menu some serious attention.

“We had to sit bolt upright or else we’d be hit. In our schoolbooks, what we now know as America was all in black. And the UK. And most of the rest of the world.”

Chris Benedict, whom I meet the following day agrees.

“And history,” she says. “We found out afterwards that things…that things were not quite as we had been told.”

Karl-Marx-Allee Boulevard

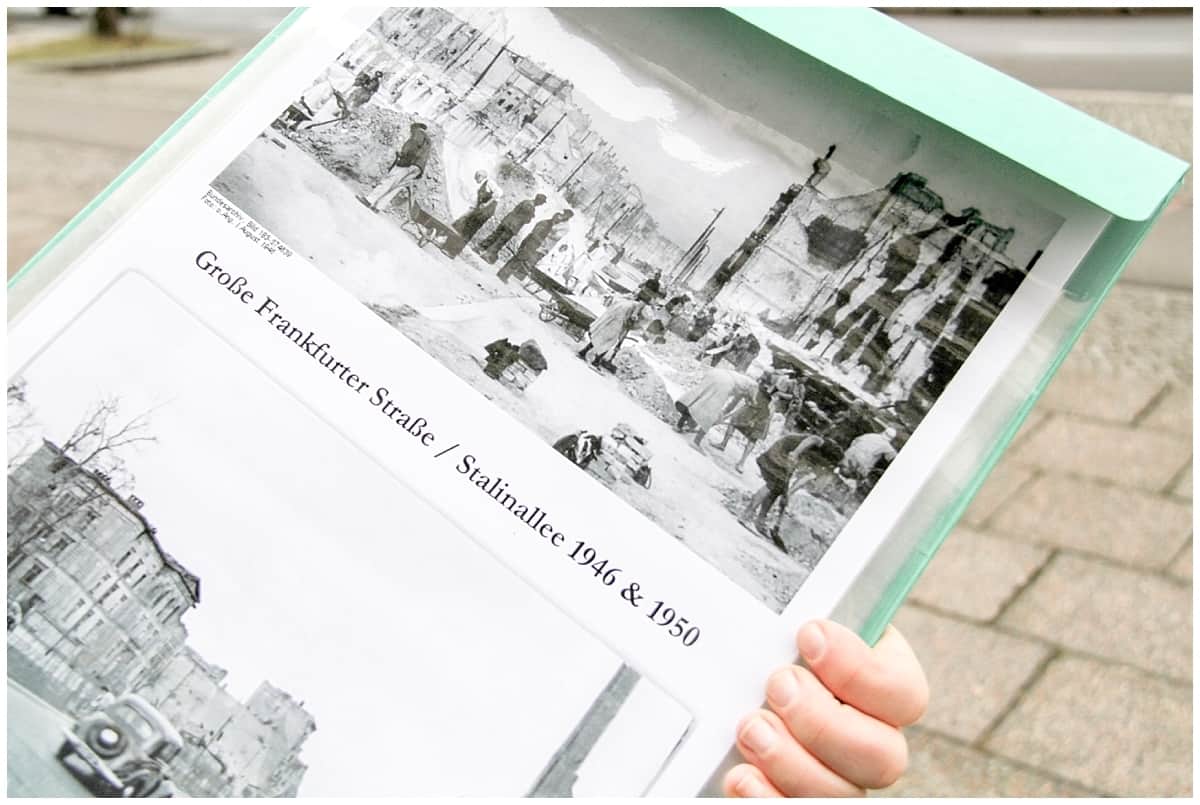

Chris gives talks about architecture and history. We meet on the controversially named Karl-Marx-Allee Boulevard outside Cafe Sibylle.

Somewhat poignantly, it’s closed.

Chris is fresh-faced and oblivious to the cold; Cafe Sybille contains Stalin’s moustache, albeit from a statue rather than the real thing, and apparently a part rather than the whole.

Karl Marx is broad, straight and more than a little bleak, but to be fair that’s probably thanks to the clouds growling overhead than to any aspect of the architecture we’re looking at.

Chris herself grew up in East Berlin. She goes a great job of pointing out the examples of Socialist Classicism and the butch ceramics that still line the buildings. She talks about the city’s 1.5 million homeless at the end of the Second World War and the competing, driving need for housing in each of the occupied zones. How Karl-Marx-Allee was the setting for the 1953 uprising, when 125 labourers lost their lives in the routine Soviet response to protests.

How this used to be called Stalin-Allee. How it follows a straight line back towards the West.

But I want to ask about the people. About her views. About the parallel life in this world that was sealed off from mine.

Another View on “Reunification” from Growing Up in East Germany

I’m wondering about how best to approach the subject when I arrive there by accident, with a clumsy question about reunification.

“Everyone talks about reunification,” she says, eyes narrowing, “as if that’s what actually happened.

“As if East was united with West. That’s not what happened.

“If that had happened we would have seen compromise. If that had happened, we would have been shown some respect, there would have been some appreciation for our values, for the things that mattered to us.

“Instead, the West talked about winning.”

Winning and Losing

This was relatively new to me. My background told me that Russia ran out of money, not to mention enthusiasm, leaving the western front to collapse on its own. My US family took me by surprise by claiming it as a victory for Uncle Sam.

One wall, two sides, multiple outlooks.

Chris, to be fair, backed up her viewpoint.

After “reunification,” everything switched to the West’s version of capitalism. Grown adults, trained to be good citizens and to work for the state, suddenly found themselves without a state. Without a job. Without money. Without healthcare. And without a clue about where to go from here.

It takes time to learn business skills. It also takes time to learn about the geography and history behind all those blacked out books.

Yet when the job applications began, it was training and exams in the West’s view of the world that mattered. East German professors fell by the wayside as those from the West took all the top spots.

Chris hugs her papers against her chest and we descend into the metro.

Growing up in East Germany and a Sense of Loss

“I look around today and I think about all we’ve lost,” she says. “Today, the message is always to make money, to buy clothes and to be selfish. There’s no sense of community any more, of helping each other out. No-one does anything now unless they think it will earn them money.”

I clear my throat, my voice wavers a little. “But wasn’t that sense of community achieved through, well, the Stasi spying on people and reporting them if they acted out of line?”

“Well, yes the Stasi did keep files. But that was to protect what we had, we had to guard the little progress we had made – and we were under constant attack from outside.”

The train doors open.

Privacy

My brain zig-zags. “But didn’t you, well, mind that people were spying on you?”

“Well, I didn’t know at the time, I was too young. But yes, the adults knew and people accepted it. Privacy wasn’t so important. It was better to give everyone an education, a job, healthcare. To protect what we had. It was only going to be temporary. We were fighting a war.”

I open my mouth and then close it again, my ignorance bubbling into the air.

I think about what she’s said. On the one hand, it sounds ridiculous. On the other, the mirror image of life today. We acquiesce to our records being kept, to being patted down by strangers at airports and many other things besides because our governments tell us we are at war. That our freedom and our way of life is under threat.

Growing up in East Germany: Different Architecture to the West

Fat drops of rain fall from the sky as we emerge in former West Berlin. We’re walking through an ambitious building project designed to compete with the Soviet-led architecture as part of the ideological and political struggle between here and StalinAllee.

In the East, the buildings were uniform; on the West, they emphasised individuality.

The rain is ugly now. Thick, bitter, fast and vicious. We take refuge in a modern church, stained glass colours hovering over our heads, blunt colours filling the edges of gloom.

My shoes squeak as I walk but beyond that, all I can hear is rain.

The Fall of the Berlin Wall

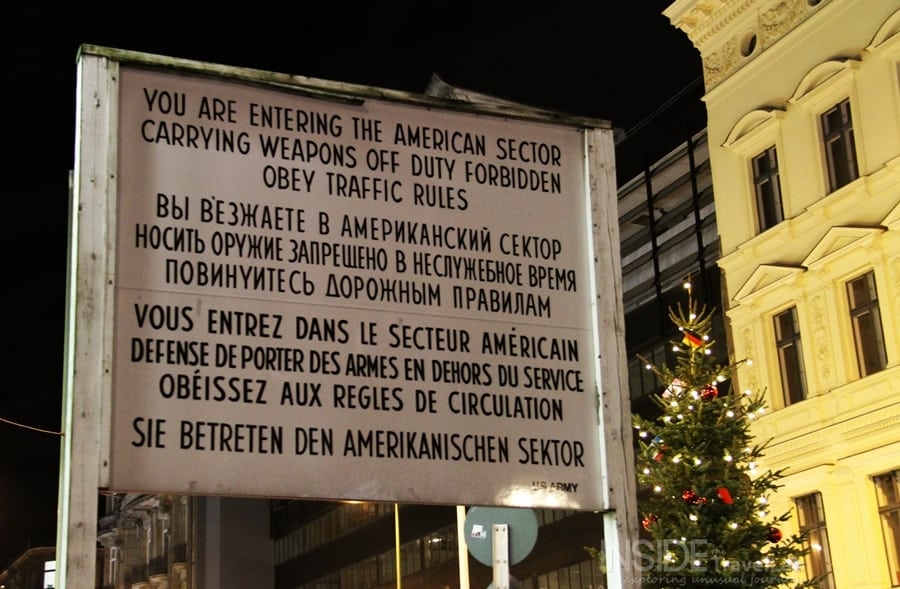

More than 20 years have passed since I first saw those pictures, the ones with graffiti on concrete, broken slabs of that political wall and animated, almost frenzied crowds shouting into the night. Twenty years since the crowd overwhelmed the guards after a mishap on the radio. Twenty years since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Until this trip, I’d always wondered why then. Why, after decades and decades of checkpoints and armed guards did the crowd suddenly decide to rush forwards and rush through.

Time at the Austro-Hungary border helped with that. So, too, did my afternoon with Julian Smith-Newman, another academic from Context.

Unlike most walls, the Berlin one was built to keep people in rather than keep people out – according to the West.

The jingle played on East German radio (available at the brilliant but cumbersomely named Berlin Wall and Memorial Documentation Centre) describes how East Germany planned to clean up their lovely Berlin by building up a wall to keep out all the nasty fascists who wanted to contaminate the good way of living.

It’s a line of thinking that I want to talk to Chris about.

Yet Another Perspective from Growing up in East Germany

“If communism brought everyone a better life, then why persecute those who wanted to leave?”

“Well, not many wanted to leave…”

“But those who did?”

“What we were told, but I was a child at the time, was that those people either didn’t really understand and needed to be retrained – like a child who runs into the road. Or…”

I can’t tell if she’s embarrassed, cautious or slightly defiant…

“Or were spies or traitors and a threat to the progress that had been made.”

Thoughts, opinions and memories shift through my mind.

What really happened after the fall of the Berlin Wall?

“But when the wall fell,” I say. “Thousands rushed to escape.”

Her eyes light up. “But they came back!”

She’s animated now. “They went to see, to have a look. To find friends and family. They were curious, it was natural.

“But most people,” she adds. “They came back.”

I think back to the event at Sopron, when refugees flooded from Hungary to Austria at the first breach of the Iron Curtain. Only East Germans fled; Hungarians stayed put.

A final question.

“Um, well, if communism works and capitalism is wrong,” I say, floating over delicate ground again. “Then why didn’t communism, well, work?”

“I don’t know,” she replies, before smiling, definitely with embarrassment this time.”Well, there is a theory…No…It doesn’t…There’s too much evidence now, but…”

“But?”

“But, well. All our lives we were told that the West was plotting to bring the system down.

“And they were.

“And they did.”

On those grounds alone, she’s in perfect agreement with my family in the US.

She grants me one more answer. “If a system is deliberately destroyed from the outside, can that really meant that it’s the system itself that doesn’t work?”

Another Perspective

Back at the chocolate house, I hear a different point of view.

Nicole is less forgiving of the Stasi – and the whole setup in general.

“I was once asked at school to name the leader of Germany,” she told me. “We had western television at home – illegally – and so I’d seen and heard a lot of what was going on.

“I gave my answer and it wasn’t Honecker.” (The leader of the GDR at that time.)

“My teacher froze. She demanded to know how I knew that name. Soon after, my parents were called to explain. Not to the school, to the authorities.”

Not a Good Little Communist

She folds her arms. “Obviously, they weren’t bringing me up like a good little communist.”

I stir my hot chocolate into an ever-increasing ellipse.

“I am sure,” says Nicole, “They are sure that I would have been taken away if this had happened one year earlier. But in 1989, there was a lot going on…Money, other issues. We received a caution.”

Nicole sits back in her chair. “You know, every now and then, my father forgets what it was really like. He looks back and says ‘well, at least everyone had a job, at least everyone got along.’”

She shakes her head. “We shouldn’t forget.”

Back in the Currywurst Museum

The currywurst museum shows a map of the city at the end of the Second World War. As it turns out, the birth of Berlin’s signature dish coincided with the birth of the Cold War.

According to legend, Herta Heuwer took the pork sausage from Germany, the ketchup from the occupying Yanks and the chilli powder from the occupying Brits (via the Indian subcontinent, I suppose) to create what is now the city’s most popular dish.

Variations then developed – and still linger – between the old lines of east and west.

“The most obscure thing,” said Chris, “is that the Wall still exists in the mind. People define themselves as East / West Berliners even 20 years later.”

And does she still view the Americans as the enemy?

She throws her head back laughing. “Well, I married one.

“We each say to each other: ‘it’s so funny, because we each grew up being told to be scared of each other and to hate each other.’

“And then we met, and both had to say, ‘Oh! So that’s what you’re really like!’”

We say goodbye and I walk off. Into a waterlogged Berlin sky.

How to Explore the History of the Berlin Wall Yourserlf

It’s entirely possible to follow a self-guided tour but you’ll get more from the experience if you travel with the right tour.

Bear in mind that there’s not “one” Berlin Wall but a series of walls, rubble, memorials and nothingness that trace where the wall used to be. And that itself is a strange, curling, curious route. It’s not as simple as a straight line separating east from west.

A Self-Guided Tour

If you visit these highlights, you’ll get a good insight into various aspects up growing up in East Germany.

- East Side Gallery in Berlin. At 1.3 kilometres long, this former marker of a divided Europe now serves as the largest open air art gallery in the world. And open air it is. Wrap up warm in the winter months. And get ready to take a LOT of street art photos. It’s free and easy to visit here. Just turn up.

- The Topography of Terror is an gallery located at the former SS headquarters which also features about 200 meters of the wall.

- Bernauer Strasse features a Berlin Wall Memorial with a visitor’s centre and information.

Get Your Guide

This online booking platform offers great flexibility (you can book in advance or at the last minute and cancel for free or until 24 hours before.) They also curate and quality-controltours so check out their tours on the Berlin wall here.

As for meeting Nicole and Yvonne? I’ll keep those friends to myself, sorry. Best of luck!

Such an interesting post! Thanks for sharing!

You’re very welcome!